With a group of popular mainstays celebrating two decades in business and a host of creative newcomers now fermenting in both the city and suburbs, it’s a bright time for the Philadelphia brewing community.

Philadelphia’s beermaking tradition is a long and rich. Many of the Founding Fathers were homebrewers, and brewpubs abounded in the city in which they navigated the tricky waters of crafting the nation — in 1793, Philly was said to be producing more beer than any other seaport in the New World. The first American lager is thought to have been brewed in a basement in the Northern Liberties section of the city in the 1840s, after Bavarian immigrant John Wagner successfully transported the cold-loving yeast across the Atlantic.

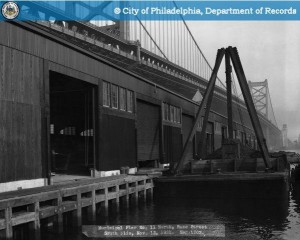

By the 1870s, there were upwards of 65 commercial brewhouses in the city — many of them in the neighborhood now known as Brewerytown — and the surrounding counties were home to hundreds more. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, Philadelphia was essentially the brewing capital of the United States — but then came the temperance movement. In the leadup to Prohibition, the city’s robust brewing industry was decimated. After Repeal, it was not among the first to bounce back.

Fast-forward to the late 1980s. In California and Colorado, the independent brewing movement was gathering steam, starting to reverse decades of industry consolidation and decline. Not so in Philly. In fact, when Schmidt’s Brewery shut down in 1987, there wasn’t a single professional beer-making operation inside the city limits. Continue reading Philly’s brewing scene: On the rise again