Today, the City of Philadelphia unveils its first street paved with porous asphalt. It may only be a tiny Bella Vista alley that rarely sees auto traffic, but it’s one of hundreds of such side streets, and it marks a milestone in part of a larger plan.

As one of America’s first cities, Philadelphia is home to one of the nation’s oldest sewers. In the time since the stormwater system was built, modern development has blanketed the region with impervious concrete and pavement. During a heavy rain or snow melt (50-60 times each year), the drainage system overflows, mixing with wastewater and dumping directly into the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers (from which the WaterWorks draws to provide our taps).

In 2009, the city finalized a plan to address the runoff overload, pledging $1.6 billion over the next 20 years. Instead of ripping up the streets to build a huge (and expensive) below-ground holding tank, the EPA approved a strategy of implementing a series of “green” stormwater infrastructure programs.

Municipal structures are being retrofitted with green roofs (and businesses and residents are encouraged to follow suit), basketball courts are being repaved with permeable concrete, parking lots are being designed to include vegetated strips and old asphalt lots are being broken up and turned into rain gardens. The idea is to turn the city’s surface into a sponge, instead of an impervious barrier. Most of these water-management techniques have been used successfully before, but not on the scale of an entire Northeastern metropolis.

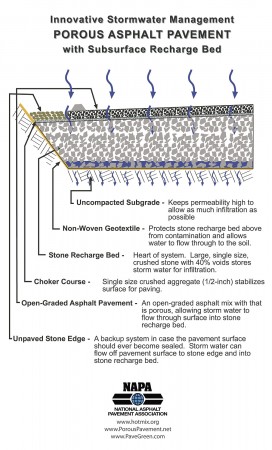

Porous asphalt is much like regular paving material, but made without the finer grains in the mix. This creates a surface with much larger gaps, through which water can seep. Beneath the blacktop is a layer of stone that acts as a reservoir, slowing down the seeping liquid even more. The street surface is still relatively smooth (smooth enough to meet ADA requirements), and because it has room to expand and contract, is much less likely to form potholes.

The Percy Street transformation cost the city $330,000, reported the Philadelphia Inquirer. The next metamorphosis is set for Webster Street between Broad and 13th, later this year

I’ve heard good things about porous cement. Should really help in areas where every parking lot drains into one overburdened creek system, e.g., Darby Creek.

Very interesting! The City of Houston (or TXDOT) repaved some freeway curves with porous asphalt last year, not for environmental reasons, but because there were places where cars routinely slid off of the freeways when it rained. The porous asphalt eliminated the pooling.

There was some concern that the benefit may have been temporary, that the pores would become clogged, though I haven’t heard anything about that since the repaving was first discussed.